Q3 Macro Outlook

Summary

Tariffs act as a tax on trade, likely slowing global economic growth and adding to short-term U.S. inflation pressures.

Policy uncertainty is prompting businesses and consumers to delay spending and investment decisions while they adopt a “wait and see” approach.

Central banks are caught between managing inflation and supporting economic growth; markets may be overly optimistic in expecting imminent interest rate cuts.

Rising government debt and deficits are drawing increased scrutiny from bond markets, leading investors to demand higher yields on longer-term bonds.

The U.S. labour market is beginning to show signs of softening, and the Sahm Rule indicator could point to a possible recession in the second half of 2025.

Confidence in U.S. economic leadership is declining, prompting investors to reassess strategies and seek greater diversification in their portfolios.

Global diversification is gaining traction, driven by slowing U.S. growth, narrowing differences in corporate earnings across regions, and a weaker U.S. dollar.

Europe and Emerging Markets (EM) are benefiting from supportive fiscal and monetary policies, coupled with relatively low investor allocations, suggesting potential for outperformance.

What’s the Outlook?

Tariffs are a tax

They lead to slower growth and higher inflation - a combination often called stagflation, which is a headache for central banks wanting to support economic activity but needing to keep a lid on inflation and inflation expectations.

Without clear policy and visibility, uncertainty remains high - weighing on corporate investment and household consumption and complicating the Fed’s (Federal Reserve) interest rate decisions.

Tariffs aren’t good for growth, productivity or efficiency

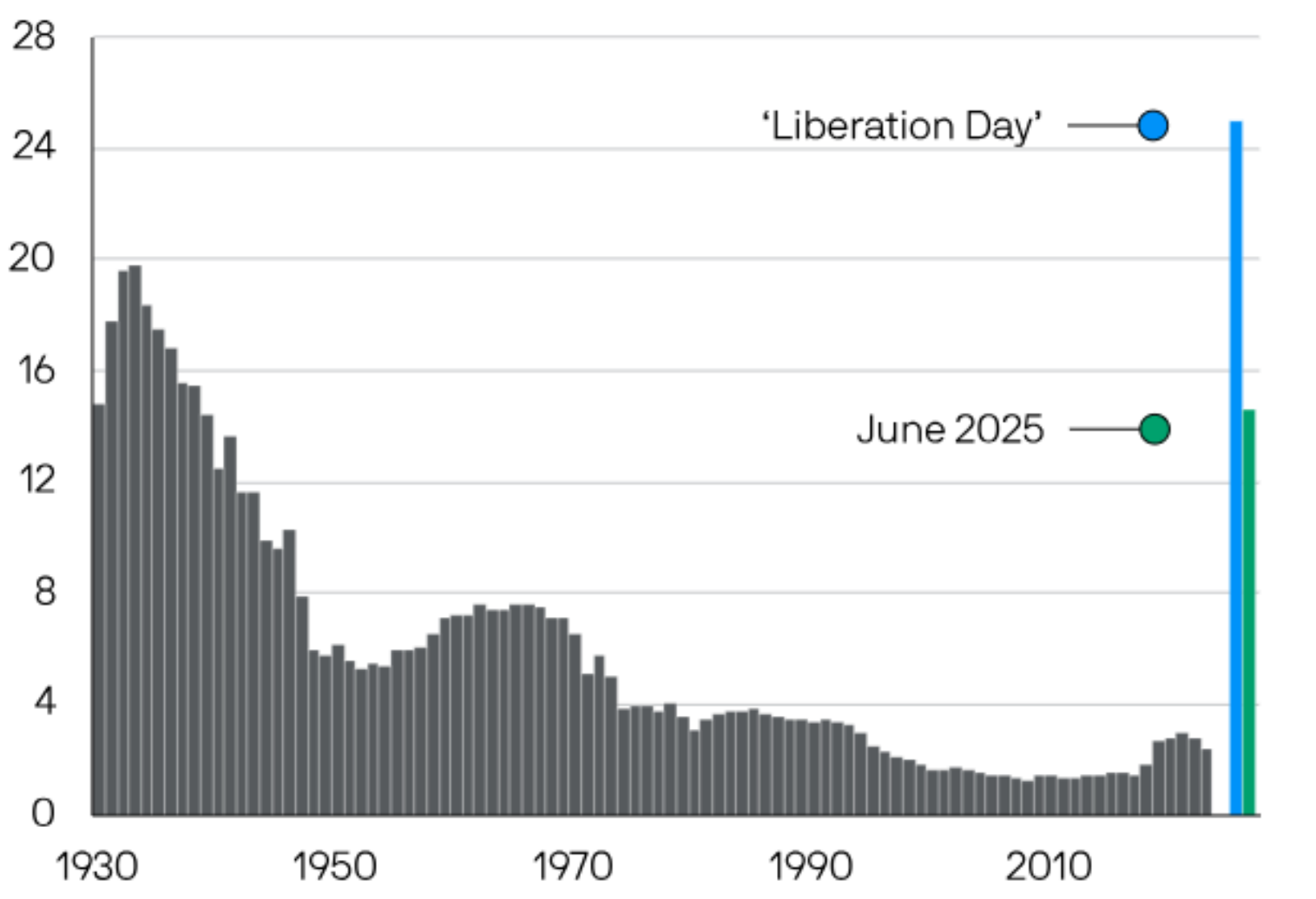

The Trump administration is expected to maintain universal tariffs of 10% which, combined with moderated reciprocal tariffs through trade agreements and negotiations, is likely to lead to an average tariff of 14-15%. The average tariff in 2024 was 2.7%, so this is a dramatic increase. It is still unclear who will bear the burden - the supplier, the importer or the consumer - but trading with the US is now harder and more expensive, which is seldom a good thing for growth.

Import Duties Collected as a Share of Total Import Value, %

Source: US effective tariff rate - Cato Institute, US Department of Commerce, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, June 2025

Markets could be becoming numb to proposed policy change. If so, they’ll no longer provide a clear signal of when the Trump administration has gone ‘too far’. This increases the risk of policy extremes and heightens the potential for policy error.

The key trade negotiations outstanding are between the US and China, and US and EU. Since the pause in reciprocal tariffs, there seems to be progress in discussions with China. As they provide 70% of smartphones, 86% of game consoles, 79% of monitors, 76% of toys, and 67% of laptops, it’s clear that the US needs China more than China needs the US. Negotiations are likely to be complex and drawn out.

Europe, on the other hand, knows it needs to compromise. Given their need for imported energy, defence equipment and more, it would be perfectly logical for a mutually beneficial way forward to be found. In reality, the EU has a large trade surplus with the US, something Trump hates, so they will need to flex, regardless of the surplus being a reflection of US consumer demand for quality European products, rather than unfair competition.

The bottom line is that uncertainty over tariffs and trade remains an on-going feature of this US government. Trump believes in tariffs, no matter the unintended consequences, and so corporates, consumers and trade partners must adapt.

This will take time to play through and there will be winners and losers in global supply chains Growth will be slower and costs higher in the US, narrowing its competitiveness with the rest of the world. As a result, investors are turning to a more globally diversified asset allocation a trend that began in the first half of 2025.

Goods previously planned for the US market are expected to get redirected elsewhere, creating deflationary pressures. That widens the scope for global macroeconomic divergence and with it variations in monetary and fiscal policy.

Big but far from beautiful – debt and deficits magnified

Current US debt-to-GDP is close to 100%. Despite delivering above-trend growth in recent years, the fiscal deficit reached 6.4% in 2024, a level typically not seen outside wartime, and certainly not when unemployment is down at just 4.2%.

This debt dynamic has sat uncomfortably with bond investors for a while, yet yields have been reasonably contained. The margin of error is now very narrow, and should the economy slow, unemployment rise and fiscal revenue contract, upward pressure on the deficit will rocket.

Compounding these worries is the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), which, according to the Congressional Budget Office is forecast to add over $3 trillion to government debt over the next 10 years. This would see the debt to GDP ratio climb to 134% by 2034 and the fiscal deficit expand to 7.5-8% per annum. With a third of government revenue needed just to pay the interest on the debt, this looks unsustainable. Heightened nervousness among bond investors is inevitable and given the relatively short debt maturity of the US, refinance risk for the debt management office rises. The result is a rising term premium - the additional compensation investors require for the risk of holding longer-term bonds - increasing the cost of servicing the debt and ultimately squeezing the availability of funding for other purposes.

Unfunded tax cuts, as contained within the proposed OBBBA, are problematic at the best of times, but with current debt and deficit levels, this looks particularly precarious.

Structural inflationary pressures can’t be ignored

The path of disinflation has stuttered in 2025 with services inflation sticky and goods deflation coming to an end. Energy and commodity prices have been helpful year-to-date, but global geopolitical risks point to these trends being skewed to the upside, despite Trump’s ‘drill baby drill’ policy aimed at increasing energy supply.

A key driver of near-term inflation is the labour market, which is so far resilient. However, new vacancies are contracting, continuing claims rising, average wage rates moderating and temporary hiring is cooling. Part of the Fed’s dual mandate is full employment, so they will be watching this closely. The expectation is that they will continue to prioritise the control of inflation and, if they need to, stomach higher levels of unemployment to keep inflation close to target.

Longer-term inflationary trends of de-globalisation, de-carbonisation, ageing demographics, rising defence expenditure and mounting debt and deficits represents a notable shift from the low inflation period post the global financial crisis of 2008/9. Interest rates are not expected to fall meaningfully, as central banks remain cautious. They want to keep real rates positive and inflation expectations under control, which is proving tricky as seen in the spike in near-term NY Fed Survey of Inflation Expectations.

Source: Haver Analytics and Fulcrum Asset Management, May 2025

Risk of recession has not gone away

Post Liberation Day on April 2nd, many economists raised their probability of recession above 50%. The subsequent pause in reciprocal tariffs, coupled with macroeconomic resilience, led forecasters to pare back those recessionary expectations.

However, we’re still facing signs of softening in the labour market, savings post-Covid are now fully exhausted, corporates are hesitant to invest and there is a real possibility of reciprocal tariffs being imposed on some countries and specific products. The risk has not gone away, nor is it priced into bond or equity markets.

For this reason, it is important to measure the health of the US consumer. Consumption makes up close to 70% of US GDP. Delinquency rates in credit cards, auto loans and student debt have been rising, but these are mostly confined to the low-income tier, so considered part of the normal economic cycle. If this broadens to the middle-income tier, the risk of recession rises and could lead to a risk-off approach among investors.

Don’t forget the Sahm Rule

At 4.2%, US unemployment sits within the Fed’s full employment range of 3.5-4.5%. However, slowing GDP growth and heightened policy uncertainty points to a probable rise in the unemployment rate. Leading independent economic forecasters believe it could climb to 4.9% by the end of 2025, way above the Fed’s forecast of 4.5%. This would trigger the Sahm Rule (when the three-month moving average of unemployment rises by 0.5% or more, relative to its low during the previous 12 months). Historically, this has been a predictor of recessions.

Dollar safe haven status doesn’t mean it can’t weaken

As the world’s global reserve currency, the dollar carries a safe haven privilege, preserving core underlying demand. However, with domestic global government bond yields higher and foreigners reducing their dollar-based asset exposure, further depreciation is possible. This tends to be supportive for non-US based assets and especially emerging markets.

US Dollar Index

Source: Bloomberg and Grizzle, April 2025

The relative outperformance of the US over recent years was built on a solid foundation of superior growth, earnings and profitability. Looking forward, the rest of the world is catching up and the US is cooling.

Structural shifts in Europe and EM

Europe’s relative outperformance at the start of the year was largely driven by attractive valuations and investors reducing their underweight positioning. Trump’s message that the US was no longer going to underpin European defence triggered a structural shift in individual country and EU policy. The release of the debt brake on German defence expenditure, coupled with a €500bn infrastructure programme and a €150bn EU defence funding programme, led to rising expectations of improved growth and productivity.

A fiscal stimulus package projected to be close to 1% of GDP per year in Germany for the next 10 years is a significant structural shift. The trickle-down effect is expected to feed into the labour market, keeping unemployment low and consumption solid. With the EU savings rate at over 15% - notably higher than the historical average - the consumer is well placed to maintain the recovery we’ve seen over the last 18 months.

Another structural shift is happening in EM. Historically associated with high levels of debt, poor fiscal discipline, elevated inflation and currency instability, the tables have turned. Inflation is well controlled, debt to GDP ratios are comfortably lower than developed market peers, fiscal prudence through Covid leaves room for expansion if/when required, and currencies are not only stable but undervalued.

Final thoughts

Economics used to drive politics. Today, politics is driving economics. Uncertainty is growing as policy changes intensify. Markets don’t like uncertainty, so increased volatility is to be expected. To help protect against this, diversification across asset classes, geographies and sectors remains key.

Disclaimer: This commentary is for general information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. It is intended to provide you with a general overview of the economic and investment landscape. It is not an offer to purchase or sell any particular asset and it does not contain all of the information which an investor may require in order to make an investment decision. We cannot accept responsibility for any loss as a result of acts or omissions taken in respect of this article.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Investments should be considered over the longer term and should fit in with your overall attitude to risk and financial circumstances. Your capital is at risk and the value of investments, as well as the income from them, can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your original investment.